The Death of a Comic Book Muse

The Death of a Comic Book Muse

From an outsider’s point of view, Margaret Thatcher was arguably the single most important political figure in the advancement of modern comics

I myself was nothing more than a tyke during Thatcher’s stranglehold, and was never impacted directly by her reign, nor was I ever part of the very heated political discourse she sparked, but even with my cursory understanding of UK politics, I was made very aware of how intense Thatcher-hate could be, simply by being a comic book fan.From an outsider’s point of view, Margaret Thatcher was arguably the single most important political figure in the advancement of modern comics.

In the 1980s, the Thatcher administration’s domestic policies, warmongering and contempt for minorities made her the satirical target of filmmakers, the punchline of songs, and the enemy of artists and poets. Comic book authors were not excluded. 2000AD, the premiere spot for British comics, was already a bastion of sci-fi satire; a place where Heavy Metal meets Phillip K. Dick by way of the Sex Pistols. So it was no great surprise to see criticisms and sly references to Thatcher pop up.

Pat Mills responded to her with one of 2000AD‘s most famous feature, Nemesis the Warlock, the story of an Earth empire far in the future under the rule of a dictatorship obsessed with exterminating alien lifeforms they deem deviant and impure, both a satire of British colonialism and an extrapolation of the Thatcher administration’s xenophobia. Over at their flagship strip, Judge Dredd, writers like John Wagner and Garth Ennis began to move the comic’s tone from its traditionally satiric Dirty Harry send-up to a more serious exploration of democracy and the title character’s own fascistic behavior as a reflection of the mood of the people reading the series (despite the fact that the Dredd stories take place in America).

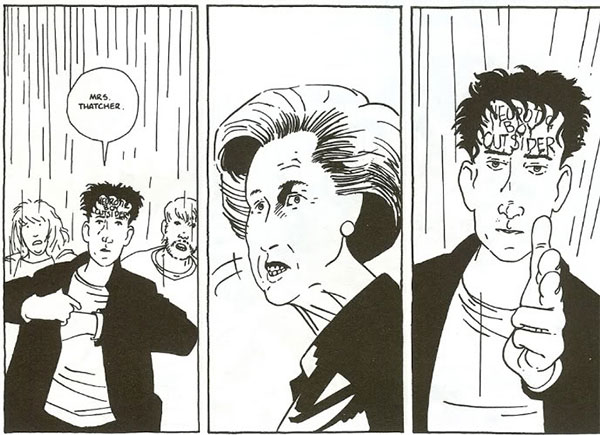

Others were more direct, like Grant Morrison’s semi-autobiographical miniseries St. Swithin’s Day, chronicling an outsider teenager’s attempt to assassinate Thatcher during a public appearance. The comic made noise in the papers and drew the condemnation of right-wing politicians.

St. Swithin’s Day, art by Paul Grist

The earliest example of these Thatcher-inspired comics was ultimately the most famous: Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s V for Vendetta, an explicit examination of the 80s brand of fascism in England, began its publication in 1982 in the pages of the short-lived British anthology comic Warrior, before it was reprinted and concluded a few years later by DC Comics.

“V for Vendetta was specifically about things like fascism and anarchy.”

“When I wrote V, politics were taking a serious turn for the worse over here. We’d had Margaret Thatcher in for two or three years, we’d had anti-Thatcher riots, we’d got the National Front and the right wing making serious advances,” Moore told MTV. “V for Vendetta was specifically about things like fascism and anarchy.”

V for Vendetta‘s notoriety and influence have only grown with time—its protagonist’s Guy Fawkes mask imitated by protesters from Anonymous to Occupy Wall Street—ironically thanks in no small part to a film adaptation that butchered and perversed the political ideas of the book. The movie, released in 2005, bizarrely transplanted the premise to a thinly-veiled parable of the post-9/11 Bush-era America, despite keeping the England setting, which Moore interpreted as political cowardice on the Wachowskis’ part (“It’s a thwarted and frustrated and perhaps largely impotent American liberal fantasy of someone with American liberal values [standing up] against a state run by neo-conservatives — which is not what V for Vendetta was about.”).

In the film, a terrorist attack scared the populace into voting for a man promising a war on terror, but it’s later discovered that the attack was a deliberate inside job designed to win over voters, which rallied the public into adopting V as a symbol of “power to the people.” In Moore’s original story, it was the general apathy of the people that allowed the fascists to come into power, not as a nightmarish dystopian anomaly, but as nothing more than the latest erosion in a long legacy of the same old story (remember that Thatcher’s party was eventually voted into power by the British public three times). So the anarchist V doesn’t bother giving the people a rallying cry to empower them—he threatens them instead.

V for Vendetta, art by David Lloyd

V for Vendetta and Watchmen can be seen as companion pieces, as they are both Alan Moore’s synopsis of the 80s political climate. If V for Vendetta was his response to Margaret Thatcher’s England, then the doomsday clock laden Watchmen was his criticism of Ronald Reagan’s America. Both of these novels, plus Moore’s gritty and tragic revamp of the old superhero property Marvelman, made possible the Frank Millerization of mainstream superhero comics, but more significantly the intellectual trend that swept over DC Comics in the second half of that decade. Erupted forth were comics with the kind of maturity—or at least the pretense of—that allowed them to fully and openly align with the New Wave counterculture youth by way of embracing surrealism, cynicism, poetry and left-wing political awareness.

It is absolutely not a coincidence that this attitude flourished during Thatcher’s terms as Prime Minister. In case you haven’t noticed, 3/4 of the best comic book writers working in American comics today are from the UK. The imported surge of talent that descended upon mainstream comics in the late 80s and early 90s was commonly referred to as the British Invasion of comics, and it can be traced back to Alan Moore’s arrival at DC, when editor Len Wein hired him to take over the fledgling Swamp Thing series. Subsequent editor Karen Berger, in what would be characteristic of the way she managed DC’s “mature readers” Vertigo imprint a decade later, gave Moore complete autonomy in revamping the character in any way he saw fit. This resulted in what is to this day the best Swamp Thing stories ever written, and one of the best Big Two runs period.

Berger recruited more British writers to do to C-list characters what Moore did to Swamp Thing, producing some of the best comics ever published by the company

Karen Berger simply cannot be thanked enough for what she has done for the industry, because after Alan Moore left DC in bad terms over Watchmen, Berger recruited more British writers to do to C-list characters what Moore did to Swamp Thing, producing some of the best comics ever published by the company: Jamie Delano’s Hellblazer, Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, Grant Morrison’s Animal Man, and Peter Milligan’s Shade the Changing Man. These titles formed the initial Vertigo line-up before there was a Vertigo, and paved the way for the stateside arrival of other popular British scribes like Mike Carey, Garth Ennis, Warren Ellis, Mark Millar, Paul Cornell, Andy Diggle, and so on. Nearly all of those authors held disdain for Thatcher (some of whom took to Twitter yesterday urging people not to mourn her), but even those who didn’t still reflected the dark atmosphere of Thatcherite wake in their writing.

The proto-Vertigo era was the grey, dreary, rain-soaked golden years of comics, shaped by the climate of the times. Under Milligan’s pen, the traditionally sci-fi hero Shade was retooled into a lovelorn poet using his powers to channel society’s psychological anxieties. Under Morrison, Animal Man fashioned himself as a PETA poster boy, championing eco-terrorist causes, animal rights and a vegan lifestyle. Then there’s Sandman, who Gaiman transformed from a pulpy crimefighter to a deity and literary icon for goth kids everywhere.

For the long-running and only recently ended Hellblazer, the early issues were just as much about the state of the country as it was about supernatural horror, with its hero’s working-class mage John Constantine displaying a particular contempt for authority figures—conservative ones especially. Delano often aligned his Constantine with hippies, environmentalists and queer folks, while battling amoral entrepreneurs and the military industrial-complex. In the third issue of the series, Constantine runs afoul of demon yuppies who play the soul stock market on the eve of the 1987 election, where apparently a third Thatcher term is deemed profitable for Hell.

Hellblazer #3, art by John Ridgway

It is impossible to imagine the kind of comics that came out in those days coming out without Thatcher being in power. I realize that this sounds like some sort of horrible apologia for her, but for an outsider like me who adores the works of art that she inspired, I am selfishly okay with how things turned out.

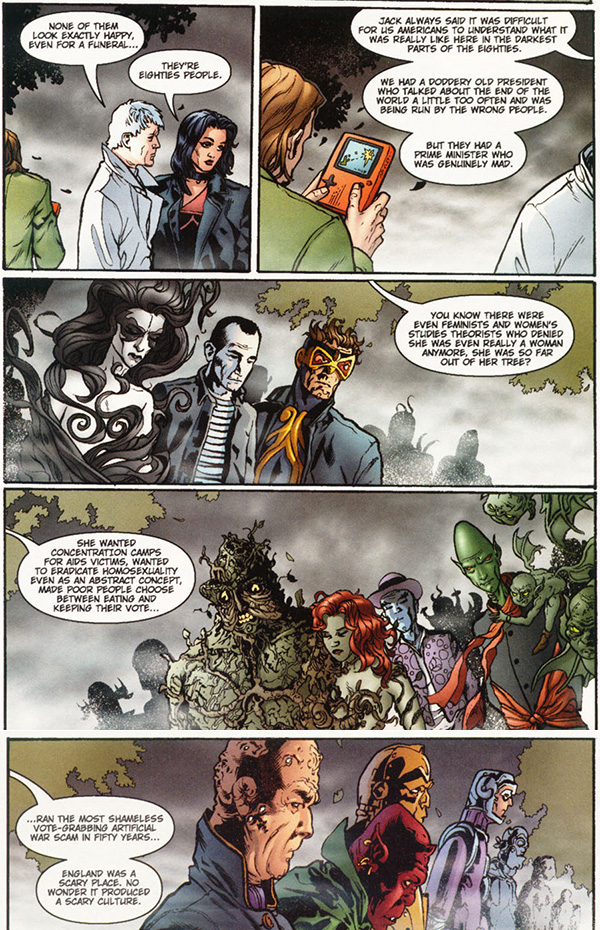

The 80s comics renaissance and Margaret Thatcher’s role in it was effectively summarized and looked back on by Warren Ellis in his and John Cassaday’s metatextual seriesPlanetary. In the 27-issue series, Ellis introduced us to a superhero team that billed themselves as “archeologists of the impossible.” What they really were are archeologists of pop culture, as the Planetary team dealt with spectacular events that mostly gave Ellis the excuse to comment on various pop culture totems, from Japanese kaijyus to John Woo movies to the Kennedy era Fantastic Four. In the series’ infamous seventh issue, Ellis gave a nostalgic tip of his hat to the Vertigo pioneers that came before him, before sending them out the door.

It starts with the funeral of Jack Carter, an English magician who is unmistakably supposed to be Constantine; a funeral attended by weird supernatural characters who bear striking resemblances to famous Vertigo mainstays. Ellis notes the morose nature of these characters, crediting Thatcher for their eternally moody disposition just as we’ve demonstrated earlier.

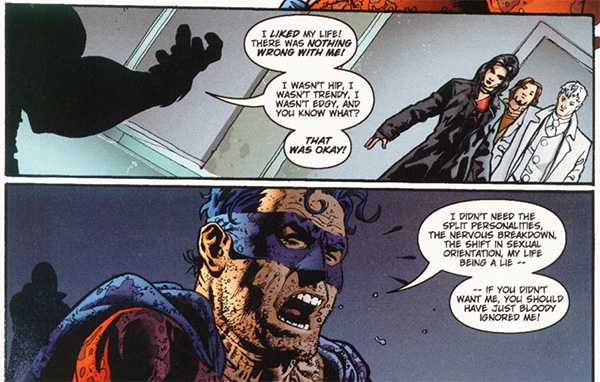

Later in the issue, when the Planetary team discovers that Carter’s death was faked, an unnamed superhero drops in to represent the aftermath of the Vertigo revolution: the aforementioned Frank Millerization of superheroes that went on to dominate the industry for much of the 1990s.

Planetary #7, art by John Cassaday

The superhero is promptly killed by Carter, who has given himself a makeover to resemble Ellis’ Transmetropolitan hero, Spider Jerusalem, and tells the Planetary team that the 80s is dead and it’s time to be someone new. If we’re to ignore the self-aggrandizement of his own creation (Ellis maintains that it was artist Cassaday’s idea), the point here seems to be that the Thatcher era comics were important, but in the end, they end up as relics of a bygone time. It’s most likely that Ellis, whose writings and online persona suggest of someone who is a bit of a champion of the zeitgeist, was simply making a general encouragement of looking at the present rather than past attitudes, but a new comic book era was being ushered in at the time of the issue’s publishing, written in a brand new cinematic voice that distanced itself from the elegiac verbiage that Alan Moore established.

Last December, Karen Berger stepped down after 20 some years of managing Vertigo. Her departure was in the aftermath of an exodus of talent allegedly prompted by the change of contract policy mandated by Time Warner/AOL a couple of years earlier in regards to the creators’ rights to sell the screen adaptations. The death blow to the imprint was the cancellation of Hellblazer so that a new toned down Constantine series could be launched within the DC universe proper. For the immediate future, Vertigo appears to be publishing only creator-owned titles by DC’s in-house superstars like Scott Snyder and Jeff Lemire, more or less just to keep them happy within the same company.

With the banner losing its relevance, the news of the death of the figure who forced it into existence feels almost expected and fitting, as if one of the final remnants of Margaret Thatcher’s lasting impact on pop culture was dissipating, and thus with it the source eventually expired.

End of an era indeed.