In the wake of the internment of Marian Price, which I believe over the last two years, can generally be agreed, to have been a form of internment because it lacked a proper, transparent trial, in a timely manner. I also believe it can be generally agreed by reasonable informed people, to have been a major setback, to what is known as the peace process in Ireland. I personally have neither been a proponent of this process or have believed it will achieve traditional Irish republican aspirations but I accept very reluctantly, it is a reality, delivered by a leadership with elements of competency, without wholesale fratricidal, blood letting.

There is an old expression, that the three long term curses of the Irish, are the English, drink and religion. From bitter personal experience I would agree, that recovery is not an overnight process, no more than a lasting peace based on justice is. The main problem accompanying the above three curses, are that to live or survive in such an environment, requires a lot of secrecy lies and generally many unhealthy, dishonest, subservient habits.

The current British occupation in Ireland, requires a considerable amount of draconian secrecy, under their Official Secrets Act and all the variations that ensues, with secret internment without trial, secret courts, and a feral secret service. This form of repression in Ireland has always been met with resistance, including physical force. To sustain resistance over any given time also requires considerable secrecy, 'rough justice,' along with violence to oppose the British Imperial violence of invasion, None of this is compatible with the necessary basic justice, that is a critical requirement of peace. Those who call for peace without this basic justice, are disingenuous and often do so from a vested interest, class based privilege. However equally, it must be also said, that after 800 years of traditional struggle, we have made little progress with our methods towars our goals.

It has been stated by experienced genuine revolutionaries, that we have a moral responsibility, to try every possible means of resistance, before the last resort of armed struggle. It is my own experience, reluctant opinion and conclusion, from bitter personal experience, that a long term campaign of guerrilla warfare, is not sustainable, successfully, in the culture of the small island of often socially incestuous, contemporary, Ireland. There are a myriad of reasons which at this point in time, would to take too long to explain this peoperly.It does however merit, considerable honest debate and discussion by genuine people, particularly of no property in Ireland.

Experience is the best teacher, but a fool will learn from no other. - Benjamin Franklin

This appears to be a very harsh statement but again from I personal experience, I have to agree. So what then is a serious alternative, to physical force politics, state terrorism and reactionary violence. I personally believe that in this age of the internet, in the absence of overbearing malign censorship,we have a tool to win our aspirations, albeit slowly and with considerable patience. Patience is for me, the best definition of the often abused word of love. Love is patient. There are many examples is Irish history, of heroic love for our island expressed by our sons and daughters. Probably the most famous recent, well known example being the death of twelve Irish hunger strikers in the present phase of struggle, there being a total of twenty two altogether. Our success depends on coming from love rather than hate, again easier said than done in an outside, mentored political environment of tit for tat divide and conquer.

It is difficult to refuse to rise to the bait of provocation and infuriating for me personally at times, as someone who sees religion, as a big part of the problem, to recognize that certain truths expressed in the Good Book, correspond perfectly with my own experience of baby steps towards the solution. The Book states, that no greater love had anyone, than to lay down their life for their friend. It also states that the truth will set us free. I believe personally, that under present circumstances, despite draconian censorship and repression, we have responsibility to try the truth rather than live by the sword. Many say the truth is is the most powerful thing on the face of this planet and personally from my own experience, I would have to agree.

Many will say on a class basis, that all of thsi it is easy to say, for someone relatively comfortable, than to have such patience, in the face of murderous imperialism and dire poverty on their doorstep. From personal experience I agree but we do have an alternative and I believe a moral responsibility, for those with potential leadership qualities, to seriously try, before resorting to armed struggle. Contemporary experience demonstrates, that terrorism begets terrorism, be it British state terrorism or reactionary violence. Having stated all of this, I believe there is a tipping point in any mass movement, with a mandate of overwhelming mass support, where there a responsibility lies with the leadership, to take the levers of power for the people, with as little bloodshed as possible.

The Truth will Set us Free in a Society as Sick as its Secrets

For those of you out there who disagree, and wish to demonstrate to me the errors of my ways, you are very welcome to do so. In the meantime I will do my best with these attempts on the internet to walk the talk. I believe every element of traditional Irish republicanism, even the Gerry Adams' flock can teach me something, so I will be quoting you. I have to say, as a non-member of Republican Sinn Fein that their traditional document, 'Eire Nua' is the best blueprint I have found, as a democratic way forward to the solution.

Going back again to the Marian Price saga, I believe Gerry Adams made a very rational remark, in the wake of Marian's release from internment. “The logic of today’s release is that Martin Corey should also befreed," Provisional Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams. In the interest of not inflaming passions further and making a serious effort to underpin a serious Peace Process with justice, the onus is on all of us, not to just pay lip service a superficial peace. This will require serious commitment, patience, tenacity and many volunteers.

To remain honest with you, it is my belief , that the status of British Occupied Ireland, cannot sustain itself in the contest of the small island of Ireland, without supremacist outsiders, engineering the cancer of sectarianism heaped on top of their class based system of inherited privilege and monarchy. I challenge them to prove me wrong. In the meantime I will try to walk the talk by quoting below an article from Wikipedia about the experience of internment being used in Ireland, in the context of trying to learn with Martin Corey's current internment without a proper trial. - Brian Clarke

Operation Demetrius

- From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- sh nationalist resistance". An Phoblacht. 9 August 2007.

- ^ a b c Malcolm Sutton's Index of Deaths from the Conflict in Ireland: 1971. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

- ^ a b c d e f Coogan, Tim Pat. The Troubles: Ireland's ordeal 1966-1996 and the search for peace. Palgrave, 2002. p.152

- ^ "Violence ebbing in Northern Ireland". The Milwaukee Journal, 13 August 1971.

- ^ Internment - Summary of Main Events. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

- ^ Hamill, D. Pig in the Middle: The Army in Northern Ireland. London, Methuen, 1985.

- ^ The Parker Report, March 1972. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

- ^ a b Ireland v. the United Kingdom Paragraph 101 and 135

- ^ Security Detainees/Enemy Combatants: U.S. Law Prohibits Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment Footnote 16

- ^ Weissbrodt, David. Materials on torture and other ill-treatment: 3. European Court of Human Rights (doc) html: Ireland v. United Kingdom, 1976 Y.B. Eur. Conv. on Hum. Rts. 512, 748, 788-94 (Eur. Comm’n of Hum. Rts.)

- ^ IRELAND v. THE UNITED KINGDOM - 5310/71 (1978) ECHR 1 (18 January 1978)

Operation Demetrius

Part of The Troubles and Operation Banner

The entrance to Compound 19, one of the sections of Long Kesh internment camp

Location Northern Ireland

Objective Arrest of suspected Irish republicanparamilitaries

Date 9–10 August 1971

04:00 – ? (UTC+01:00)

Executed by

British Army

British Army Royal Ulster Constabulary

Royal Ulster ConstabularyOutcome 342 people arrested and interned

7,000 civilians displaced

Casualties (see below)

[show]

v

t

e

The Troubles

Operation Demetrius was a British Army operation in Northern Ireland on 9–10 August 1971, during The Troubles. It involved the mass arrest andinternment (without trial) of 342 people suspected of being involved with Irish republican paramilitaries (the Provisional IRA and Official IRA). Armed soldiers launched dawn raids throughout Northern Ireland, sparking four days of rioting that killed 20 civilians, two Provisional IRA members and two British soldiers. About 7,000 people fled their homes, of which roughly 2,500 fled south of the border. No loyalist paramilitaries were included in the sweep and many of those who were arrested had no links with republican paramilitaries, which caused much anger. The policy of internment was to last until December 1975 and during that time 1,981 people were interned.[1] Its introduction, and the abuse of those interned, led to numerous protests and a sharp increase in violence. The interrogation techniques used on the internees were described by the European Commission of Human Rights in 1976 as "torture", but theEuropean Court of Human Rights ruled on appeal in 1978 that while the techniques were "inhuman and degrading", they did not constitute torture.[2]

Contents [hide]

1 Planning

2 Legal basis

3 The operation and its immediate aftermath

4 Long-term effects

5 Effects on domestic and international law

5.1 Parker Report

5.2 European Commission of Human Rights

5.3 European Court of Human Rights

6 References

Planning [edit]

Internment was re-introduced on the orders of the then Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Brian Faulkner. The policy of internment had been used a number of times during Northern Ireland's (and the Republic of Ireland's) history.

In the case brought to the European Commission of Human Rights by the Irish Government against the United Kingdom, it was conceded that Operation Demetrius was planned and implemented from the highest levels of the British Government and that specially trained personnel were sent to Northern Ireland to familiarize the local forces in what became known as the 'five techniques', described by opponents as "a euphemism for torture".[3]

On the initial list of those to be arrested, which was drawn up by RUC Special Branch and MI5, there were 450 names, but only 350 of these were able to be arrested. Key figures on the lists, and many who never appeared on them, were warned before the swoop began. It included leaders of the non-violent civil rights movement such as Ivan Barr and Michael Farrell. But, as Tim Pat Coogan noted,

What they did not include was a single Loyalist. Although the UVF had begun the killing and bombing, this organisation was left untouched, as were other violent Loyalist satellite organisations such as Tara, the Shankill Defence Associationand the Ulster Protestant Volunteers. It is known that Faulkner was urged by the British to include a few Protestants in the trawl but he refused.[4]

It was agreed to introduce internment at a meeting between Faulkner and UK Prime Minister Edward Heath in August 5, 1971. The British cabinet recommended, “balancing action”, such as the arrest of loyalist militants, the calling in of weapons held by (generally unionist) rifle clubs in Northern Ireland and the indefinite ban on parades, particularly those by the Orange Order. However Faulkner argued that a ban on parades was unworkable, the gun clubs posed no security risk and there was no evidence of loyalist terrorism. It was eventually agreed that there would be a six-month ban on parades but no targeting of loyalists and that internment would go ahead on August 9, in an operation carried out by the Army.[5]

Legal basis [edit]

The internments were initially carried out under Regulations 11 and 12 of 1956 and Regulation 10 of 1957 (the Special Powers Regulations), made under the authority of the Special Powers Act. The Detention of Terrorists Order of 7 November 1972, made under the authority of the Temporary Provisions Act, was used after direct rule was instituted.

The operation and its immediate aftermath [edit]

The HMS Maidstone, a prison ship docked at Belfast where many internees were sent

The HMS Maidstone, a prison ship docked at Belfast where many internees were sentOperation Demetrius began on Monday 9 August at about 4AM.

The operation was in two parts:

(1) Arrest and movement of the detainees to one of three regional holding centers: Girdwood in Belfast, Ballykinler in County Down, or Magilligan in County Londonderry.

(2) The process of identification and questioning, leading either to release of the detainee or movement into detention at Crumlin Road prison or aboard the HMS Maidstone, aprison ship in Belfast Harbor.[6]

In the first wave of raids across Northern Ireland, 342 people were arrested.[7] Many of those arrested reported that they and their families were assaulted, verbally abused and threatened by the soldiers. There were claims of soldiers smashing their way into houses without warning and firing rubber bullets through doors and windows. Many of those arrested also reported being ill-treated during their detention. They complained of being beaten, verbally abused, threatened, harassed by dogs, denied sleep, and starved. Specific humiliations included being forced to run a gauntlet of baton-wielding soldiers, having their heads forcefully shaved, being kept naked, being burnt with cigarettes, having a sack placed over their heads for long periods, having a rope kept around their necks, having the barrel of a gun pressed against their heads, being dragged by the hair, being trailed behind armored vehicles while barefoot, and being tied to armored trucks as a human shield.[8][9]

The operation sparked an immediate upsurge of violence, which was said to be the worst since the August 1969 riots.[7] The British Army came under sustained attack from Irish nationalist/republican rioters and gunmen, especially in Belfast. According to journalistKevin Myers: "Insanity seized the city. Hundreds of vehicles were hijacked and factories were burnt. Loyalist and IRA gunmen were everywhere".[10] People blocked roads and streets with burning barricades to stop the British Army entering their neighborhoods. InDerry, barricades were again erected around Free Derry and "for the next 11 months these areas effectively seceded from British control".[11] Between 9 and 11 August, 24 people were killed or fatally wounded: 20 civilians (14 Irish Catholics, 6 Protestants), two members of the Provisional IRA, shot dead by the British Army, and two members of the British Army, shot dead by the Provisional IRA.[12]

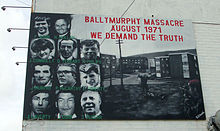

A mural commemorating those killed in theBallymurphy Massacre during Operation Demetrius

A mural commemorating those killed in theBallymurphy Massacre during Operation DemetriusOf the civilians killed, 17 were killed by the British Army and the other three were killed by unknown attackers.[12] In West Belfast's Ballymurphy housing estate, 11 Irish Catholic civilians were killed by the British Army between 9 and 11 August in an episode that has become known as the Ballymurphy Massacre. Another flashpoint was Ardoyne in North Belfast, where soldiers shot dead three people on 9 August.[12] Many Protestant families fled Ardoyne and about 200 burnt their homes as they left, lest they "fall into Catholic hands".[13] Protestant and Catholic families fled "to either side of a dividing line, which would provide the foundation for the permanent peaceline later built in the area".[10] Catholic homes were burnt in Ardoyne and elsewhere too.[13] About 7000 people, most of them Catholic, were left homeless.[13] About 2500 Catholic refugees fled south of the border, where newrefugee camps were set up.[13]

By 13 August, media reports indicated that the violence had begun to wane, seemingly due to exhaustion on the part of the IRA and security forces.[14]

On 15 August, the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) announced that it was starting a campaign of civil disobedience in response to the introduction of internment. By 17 October, it was estimated that about 16,000 households were withholding rent and rates for council houses as part of the campaign of civil disobedience.[7]

On 16 August, over 8000 workers went on strike in Derry in protest at internment. Joe Cahill, then Chief of Staff of the Provisional IRA, held a press conference during which he claimed that only 30 Provisional IRA members had been interned.[7]

On 22 August, in protest against internment, about 130 non-Unionist councillors announced that they would no longer sit on district councils. The SDLP also withdrew its representatives from a number of public bodies.[7] On 19 October, five Northern Ireland Members of Parliament (MPs) began a 48-hour hunger strike against internment. The protest took place near 10 Downing Street in London. Among those taking part were John Hume, Austin Currie, and Bernadette Devlin.[7] Protests would continue until internment was ended in December 1975.

Long-term effects [edit]

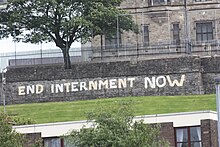

Anti-internment mural in the Bogside area of Derry

Anti-internment mural in the Bogside area of DerryThe backlash against internment contributed to the decision of the British Government under Prime Minister Edward Heath to suspend the Northern Ireland Government and replace it with direct rule from Westminster, under the authority of a British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.

Following the resignation of the Government of Northern Ireland and the prorogation of theParliament of Northern Ireland in 1972, internment was continued by the direct ruleadministration until 5 December 1975. During this time a total of 1,981 people were interned: 1,874 were from a Catholic or Irish nationalist background, while 107 were from a Protestant or Ulster loyalist background.[15]

Historians generally view the period of internment as inflaming sectarian tensions in Northern Ireland, while failing in its goal of arresting key members of the IRA. Many of the nationalists arrested had no links whatsoever with the IRA, but their names appeared on the list of those to be arrested through bungling and incompetence. The list's lack of reliability and the arrests that followed, complemented by reports of internees being abused, led to more people identifying with the IRA in the nationalist community and losing hope in other methods. After Operation Demetrius, recruits came forward in huge numbers to join the Provisional and Official wings of the IRA.[13] Internment also led to a sharp increase in violence. In the eight months before the operation, there were 34 conflict-related deaths in Northern Ireland. In the four months following it, 140 were killed.[13] A serving officer of the British Royal Marines declared:

It (internment) has, in fact, increased terrorist activity, perhaps boosted IRA recruitment, polarised further the Catholic and Protestant communities and reduced the ranks of the much needed Catholic moderates.[16]

In terms of loss of life, 1972 was the most violent of the Troubles. The fatal march on Bloody Sunday (30 January 1972) in Derry, when 14 unarmed civil rights protesters were shot dead by British paratroopers, was an anti-internment march.

Effects on domestic and international law [edit]

Parker Report [edit]

When the interrogation techniques used on the internees became known to the public, there was outrage at the Government, especially from the Irish nationalist community. In answer to the anger from the public and Members of Parliament, on 16 November 1971 (just over a month after the start of the operation), the British Government commissioned a committee of inquiry chaired by Lord Parker (theLord Chief Justice of England) to look into the legal and moral aspects of the 'five techniques'.

The "Parker Report"[17] was published on 2 March 1972 and found the five techniques to be illegal under domestic law:

10. Domestic Law ...(c) We have received both written and oral representations from many legal bodies and individual lawyers from both England and Northern Ireland. There has been no dissent from the view that the procedures are illegal alike by the law of England and the law of Northern Ireland. ... (d) This being so, no Army Directive and no Minister could lawfully or validly have authorized the use of the procedures. Only Parliament can alter the law. The procedures were and are illegal.

On the same day (2 March 1972), United Kingdom Prime Minister Edward Heath stated in the House of Commons:

[The] Government, having reviewed the whole matter with great care and with reference to any future operations, have decided that the techniques ... will not be used in future as an aid to interrogation... The statement that I have made covers all future circumstances.[18]

As foreshadowed in the Prime Minister's statement, directives expressly forbidding the use of the techniques, whether alone or together, were then issued to the security forces by the Government.[18] These are still in force and the use of such methods by UK security forces would not be condoned by the Government.

European Commission of Human Rights [edit]

The Irish Government, on behalf of the men who had been subject to the five techniques, took a case to the European Commission on Human Rights (Ireland v. United Kingdom, 1976 Y.B. Eur. Conv. on Hum. Rts. 512, 748, 788-94 (Eur. Comm’n of Hum. Rts.)). The Commission stated that it

...unanimously considered the combined use of the five methods to amount to torture, on the grounds that (1) the intensity of the stress caused by techniques creating sensory deprivation "directly affects the personality physically and mentally"; and (2) "the systematic application of the techniques for the purpose of inducing a person to give information shows a clear resemblance to those methods of systematic torture which have been known over the ages...a modern system of torture falling into the same category as those systems applied in previous times as a means of obtaining information and confessions.[19][20]

European Court of Human Rights [edit]

The Commissions findings were appealed. In 1978, in the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) trial Ireland v. the United Kingdom(Case No. 5310/71),[21] the facts were not in dispute and the judges court published the following in their judgement:

These methods, sometimes termed "disorientation" or "sensory deprivation" techniques, were not used in any cases other than the fourteen so indicated above. It emerges from the Commission's establishment of the facts that the techniques consisted of:

(a) wall-standing: forcing the detainees to remain for periods of some hours in a "stress position", described by those who underwent it as being "spreadeagled against the wall, with their fingers put high above the head against the wall, the legs spread apart and the feet back, causing them to stand on their toes with the weight of the body mainly on the fingers";

(b) hooding: putting a black or navy coloured bag over the detainees' heads and, at least initially, keeping it there all the time except during interrogation;

(c) subjection to noise: pending their interrogations, holding the detainees in a room where there was a continuous loud and hissing noise;

(d) deprivation of sleep: pending their interrogations, depriving the detainees of sleep;

(e) deprivation of food and drink: subjecting the detainees to a reduced diet during their stay at the centre and pending interrogations.

These (a to e) were the 'five techniques' referred to above. The court ruled:

167. ... Although the five techniques, as applied in combination, undoubtedly amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment, although their object was the extraction of confessions, the naming of others and/or information and although they were used systematically, they did not occasion suffering of the particular intensity and cruelty implied by the word torture as so understood. ... 168. The Court concludes that recourse to the five techniques amounted to a practice of inhuman and degrading treatment, which practice was in breach of [the European Convention on Human Rights] Article 3 (art. 3).

On 8 February 1977, in proceedings before the ECHR, and in line with the findings of the Parker Report and UK Government policy, the Attorney-General of the United Kingdom stated:

The Government of the United Kingdom have considered the question of the use of the 'five techniques' with very great care and with particular regard to Article 3 (art. 3) of the Convention. They now give this unqualified undertaking, that the 'five techniques' will not in any circumstances be reintroduced as an aid to interrogation.

References [edit]

^ Joint Committee on Human Rights, Parliament of the United Kingdom (2005). Counter-Terrorism Policy And Human Rights: Terrorism Bill and related matters: Oral and Written Evidence. Counter-Terrorism Policy And Human Rights: Terrorism Bill and related matters 2. The Stationery Office. p. 110.

^ http://www.worldlii.org/eu/cases/ECHR/1978/1.html

^ Parker, Tom. Frontline: "Is torture ever justified?". PBS.

^ Coogan, Tim Pat. The Troubles: Ireland's ordeal 1966-1996 and the search for peace. London: Hutchinson. p.126Internment - Summary of Main Events

^ The Irish Story - Internment is introduced in Northern Ireland

^ The Compton Report, November 1971. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

^ a b c d e f Internment: A chronology of the main events.Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

^ Danny Kennally and Eric Preston. Belfast August 1971: A Case to be Answered. Independent Labour Party, 1971.Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN).

^ Danny Kennally and Eric Preston. Belfast August 1971: A Case to be Answered. Chapter: Treatment of Arrested. Independent Labour Party, 1971. Conflict Archive on the Internet(CAIN).

^ a b McKittrick, David. Lost Lives: The stories of the men, women and children who died through the Northern Ireland Troubles. Mainstream, 1999. p.80

^ "Blunt weapon of internment fails to cru

No comments:

Post a Comment